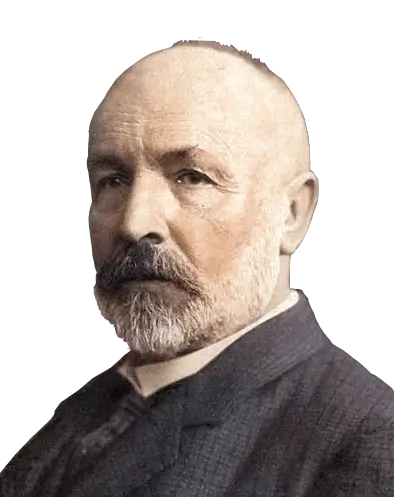

Cantor’s religious beliefs and his transfinite numbers

Page last updated 27 Feb 2022

How much of Georg Cantor’s invention of transfinite numbers arose on account of his religious beliefs? A recent study of the relationship between the reasoning process of an individual and their religiosity suggested that the results “accord closely with the hypothesis that religious dogmatism correlates with a cognitive-behavioral tendency to forgo logical problem solving when an intuitive answer is available.” Richard E Daws & Adam Hampshire, “The negative relationship between reasoning and religiosity is underpinned by a bias for intuitive responses specifically when intuition and logic are in conflict”, Frontiers in Psychology 8, 2017.

Was this the case with Georg Cantor? A vast amount of literature has been written about Cantor and his religious beliefs, but rather than add further unnecessary verbiage, we can let Cantor’s own words speak for him. Cantor was in frequent written communication with high ranking religious leaders regarding connections between his notions of the infinite and how that could be considered to be in harmony with the notion of a god that has capabilities that are infinite. The result is that there is a sizable stack of Cantor’s writings about god, numbers and sets, of which only a small selection is included below:

Georg Cantor professes his conviction that his notion of the transfinite, and the reality of its actual existence, follow directly from god: Letter from Cantor to Cardinal Franzelin Halle January 22, 1886, as in Georg Cantor, Briefe, H. Meschowski, and W. Nilson, eds., Berlin: Springer, 1991, p 255, my translation.

One proof [of the reality of the transfinite] proceeds from the concept of God and infers from the greatest perfection of God’s essence the possibility of the creation of a transfinite order, from his supreme goodness to the necessity of the creation of the transfinite.

Cantor sets out in some detail his justification of his notion of the transfinite by appealing to aspects of a god that he believes in: Letter from Cantor to Jeiler (1888), pp.414-417 in Tapp, Christian, and Georg Cantor. Kardinalität und Kardinäle: wissenschaftshistorische Aufarbeitung der Korrespondenz zwischen Georg Cantor und katholischen Theologen seiner Zeit, Vol. 53, Franz Steiner Verlag, 2005, translation by Joanna Van Der Veen & Leon Horsten in “Cantorian infinity and philosophical concepts of god”, European journal for philosophy of religion 5.3 (2013): pp.117-138.

God knows infinitely many things in reality and categorically outside Himself (possible objects, objects that occur throughout the time series in the future), that admittedly do not always occur together on the side of the things, but that do have a simultaneity in their being known in God’s Intellect. If only one would have convinced oneself always of this secure and unshakable proposition in its full content (I mean, not just in general, but also in special and concrete cases), then one would have recognized in it without any trouble the truth of the transfinite, and millennia of disputes and errors would have been avoided.

If we now apply this proposition to a special class of objects of God’s intellect, then we arrive at the elements (elementary propositions) of the theory of infinite numbers and order types.

Every single finite cardinal number (1 or 2 or 3, etc) is contained in God’s Intellect both as an exemplary idea, and as a unitary form of knowledge of countless compound objects, to which the cardinal number applies: all finite cardinal numbers are therefore distinctly and simultaneously present in God’s mind (Augustine 2003: book XII, Chapter 19: ‘Against those, who say that, what is infinite, can also not be comprehended by God’s knowledge’). Actually Cantor’s reference should be to Chapter 18, not Chapter 19.

They build in their totality a manifold, unified, and from the other contents of God’s Intellect separated thing in itself, that itself forms an object of God’s Knowledge. But since the knowledge of a thing presupposes a unitary form, by which this thing exists and is known, there must in God’s intellect be a determinate cardinal number available, which relates itself to the collection or totality of all finite cardinals in the same way as the number 7 relates itself to the notes in an octave.

For this, which can be shown to be the smallest transfinite cardinal number, I have chosen the sign .

On the other hand the finite cardinal numbers 1, 2, 3, … form in their natural order a well-ordered collection […]; the general form, under which this well-ordered collection of all finite cardinal numbers is necessarily conceived by God’s Intellect (on reflection on them belonging to the ordering that I have just described), I call the ordinal number of this well-ordered collection, or its order type, and I signify it with ω; here, too, it can easily be shown that ω is the smallest transfinite ordinal number.

When we abstract in ω from the ordering of its elements (which are then just units), then we will naturally obtain the cardinal number that we have denoted above by .

This is to explain my notation; the bar over the ω should remind of the abstraction from the ordering of the elements in the cardinal number ; one can say, that the cardinal number originates from the ordinal number ω, when we abstract in the latter from the ordering of the units that are contained in it.

Cantor states that his ideas on set theory arise from metaphysical beliefs: Pages 309-310 in Tapp, Christian, and Georg Cantor. Kardinalität und Kardinäle: wissenschaftshistorische Aufarbeitung der Korrespondenz zwischen Georg Cantor und katholischen Theologen seiner Zeit, Vol. 53, Franz Steiner Verlag, 2005, translation by Joanna Van Der Veen & Leon Horsten in “Cantorian infinity and philosophical concepts of god”, European journal for philosophy of religion 5.3 (2013): pp.117-138.

The general theory of manifolds … belongs entirely to metaphysics. You can easily convince yourself from this, when you examine the categories of cardinal number and ordinal type, these fundamental concepts of set theory, with respect to the degree of their generality and besides will remark, that in them thought is completely pure, so that there is not even the least scope for the imagination to play a role. This is not altered in the least by the images, to which I, like all metaphysicians, from time to time help myself, and also the fact that the works of my pen are published in mathematical journals, does not modify the metaphysical content and character of them.

In a letter of 1883 Cantor claims that he is only a vessel by which eternal truths are communicated: Letter from Cantor to Gösta Mittag-Leffler Halle, Dec. 23, 1883, as in Georg Cantor, Briefe, H. Meschowski, and W. Nilson, eds., Berlin: Springer, 1991, p 160, my translation.

I am far from claiming my discoveries are due to personal merit, because I am only an instrument of a higher power that will continue to work long after me, just as it revealed itself thousands of years ago to Euclid and Archimedes.

Cantor suggests that his mathematics will lead to a greater understanding of god: From a letter from Georg Cantor to A. Eulenberg, Feb. 28, 1886, as in Gesammelte Abhandlungen mathematischen und philosophischen Inhalts, Georg Cantor, ed by Ernst Zermelo, Springer-Verlag, 2013, translation by Gabriele Chaitkin in On the Theory of the Transfinite.

The Transfinite with its abundance of formations and forms, points with necessity to an Absolute, to the “truly Infinite”, to whose Magnitude nothing can be added or subtracted and which therefore is to be seen quantitatively as absolute Maximum. The latter exceeds, so to speak, the human power of comprehension and eludes particularly mathematical determination; whereas the Transfinite not only fills the vast field of the possible in God’s knowledge, but also offers a rich, constantly increasing field of ideal inquiry and attains reality and existence, I am convinced, also in the world of the created, up to a certain degree and in different relations, to bring the Magnificence of the Creator, following His absolute free decree, to greater expression than could have occurred through a merely “finite world”. This will, however, have to wait a long time for general recognition, especially among the theologians, as valuable as this knowledge would prove to be as a resource for the promotion of their domain (religion).

Cantor also claims that the transfinite occurs in some way in the real world: From Mitteilungen zur Lehre vom Transfiniten (Communications on the theory of the transfinite), section V, Zeitschrift für Philosophie und philosophische Kritik 91, pp.81–125; 92 (1887), as in pp.405–406, Gesammelte Abhandlungen: mathematischen und philosophischen Inhalts, ed Zermelo, Springer-Verlag, republished, 2013, my translation.

The transfinite with its abundance of shapes and forms necessarily points to an absolute, to the “truly infinite”, the size of which cannot be added or decreased and which is therefore to be considered in quantitative terms as the absolute maximum. The latter to some extent exceeds human comprehension and above all eludes a mathematical determination; whereas the transfinite not only fills the wide area of what is possible in God’s knowledge, but it also offers a rich, ever-increasing field of ideal research and in my opinion, in the created world it also occurs to a certain extent in various relationships to reality and existence, in order to express the glory of the Creator according to his absolutely free will, more strongly than it could have happened through a mere “finite world”.

Cantor claims that the transfinite is god’s invention; Letter from Cantor to Jeiler (13 October 1895), p 427 in Tapp, Christian, and Georg Cantor. Kardinalität und Kardinäle: wissenschaftshistorische Aufarbeitung der Korrespondenz zwischen Georg Cantor und katholischen Theologen seiner Zeit, Vol. 53, Franz Steiner Verlag, 2005, as in p 218 of “Idealist and realist elements in Cantor’s approach to set theory” by Ignasi Jané, Philosophia Mathematica 18.2 (2010): pp.193-226.

The transfinite is capable of multiple formations, specifications and individuations. In particular, there are transfinite cardinal numbers and transfinite ordinal numbers, which possess a mathematical regularity as definite and as humanly researchable as the finite numbers and forms. All these particular modes of the transfinite exist from eternity as ideas in the divine intellect.

In case it might be thought that perhaps Cantor was simply a man of his time, no more or no less religious than the average person of that era, the mathematician Gerhard Kowalewski, who had quite regular contact with Cantor in the 1890’s, wrote in his autobiography that: Gerhard Kowalewski (1876 - 1950), Bestand und Wandel, Oldenbourg Wissenschaftsverlag, Munich 1950, p. 107 and p. 200 respectively, my translations.

“Cantor was a deeply religious person. What he experienced while building his set theory moved his innermost soul.”

and:

“These cardinal numbers, the Cantorian Alephs, were something sacred for Cantor, in a sense the steps that lead up to the throne of infinity, to the throne of God. According to his convictions, all conceivable cardinal numbers were populated by these Alephs.”

And in an article of 1887, Cantor quotes an entire chapter from St. Augustine, in Latin, here is a translated excerpt: St. Augustine, De Ovitate Dei in Latin, Book XII, Chapter 19, quoted in Cantor’s Mitteilungen zur Lehre vom Transfiniten 1, II (Communications on the theory of the transfinite), Zeitschrift fur Philosophie und philosophische Kritik. English translation by Henry Bettenson, City of God, Penguin, Harmondsworth, 1972, pp.496-497.

Every number is defined by its own unique character, so that no number is equal to any other. They are all unequal to one another and different, and the individual numbers are finite but as a class they are infinite. Does that mean that God does not know all numbers, because of their infinity? Does God’s knowledge extend as far as a certain sum, and end there? No one could be insane enough to say that.

Never let us doubt, then, that every number is known to him ‘whose understanding cannot be numbered’. Although the infinite series of numbers cannot be numbered, this infinity of numbers is not outside the comprehension of him ‘whose understanding cannot be numbered’. And so, if what is comprehended in knowledge is bounded within the embrace of that knowledge, and thus is finite, it must follow that every infinity is, in a way we cannot express, made finite to God, because it cannot be beyond the embrace of his knowledge.

Therefore, if the infinity of numbers cannot be infinite to the knowledge of God, in which it is embraced, who are we men to presume to set limits to his knowledge, by saying that if temporal things and events are not repeated in periodic cycles, God cannot foreknow all things which he makes, with a view to creating them, or know them all after he has created them? In fact his wisdom is multiple in its simplicity, and multiform in its uniformity. It comprehends all incomprehensible things with such incomprehensible comprehension that if he wished to create new things of every possible kind, each of them unlike its predecessor, none of them could be for him undesigned and unforeseen, nor would it be that he foresaw each just before it came into being; God’s wisdom would contain each and all of them in his eternal prescience.

For further reading, you can read some of Cantor’s religious/

In his first reply Cardinal Franzelin suggests that Cantor may be suggesting Pantheism, which would be unacceptable to the church.

Cantor protests against this stating that:

“… no system is further removed from my essential beliefs than pantheism, apart from materialism, with which I have absolutely nothing in common.”

Cardinal Franzelin replies again, this time rebuking Cantor for suggesting that the transfinite is necessarily created (as in the quotation above of 22 Jan 1886) since that would imply that god has no choice in the creation of infinities.

Cantor’s response is that what he actually meant was not that god was bound by any necessity, but that is necessary for humans to recognize that god created not only the infinite but also the transfinite.

You can read online an English translation of one of Cantor’s major works, Grundlagen einer allgemeinen Mannigfaltigkeitslehre (Foundations of a general theory of sets), which lays out his philosophy on different sizes of infinity and transfinite numbers, and the page The Origins of Transfinite Numbers gives the details of the process by which Cantor arrived at his notion of transfinite numbers. For an overview of current set theories, see the overview that starts at Overview of set theory: Part 1: Different types of set theories.

Are transfinite numbers necessary in maths?

Some mathematicians are so enamored with transfinite numbers that attempt to justify disregarding the religious origins in various ways - one such way is their belief that transfinite ordinal numbers are necessary to obtain certain results. One such result is that a Goodstein sequence always terminates by reaching zero; Reuben Goodstein wrote a proof to this effect that was based on transfinite numbers. Since that time, many mathematicians appear to believe that it is impossible to prove that result without using transfinite numbers, but in fact there is a straightforward proof that Goodstein sequences always terminate and which does not use transfinite numbers at all, see A Proof of Goodstein’s Theorem without Transfinite numbers.

Rationale: Every logical argument must be defined in some language, and every language has limitations. Attempting to construct a logical argument while ignoring how the limitations of language might affect that argument is a bizarre approach. The correct acknowledgment of the interactions of logic and language explains almost all of the paradoxes, and resolves almost all of the contradictions, conundrums, and contentious issues in modern philosophy and mathematics.

Site Mission

Please see the menu for numerous articles of interest. Please leave a comment or send an email if you are interested in the material on this site.

Interested in supporting this site?

You can help by sharing the site with others. You can also donate at where there are full details.

where there are full details.