Is Mathematics Unreasonably Effective?

Page last updated 28 Aug 2021

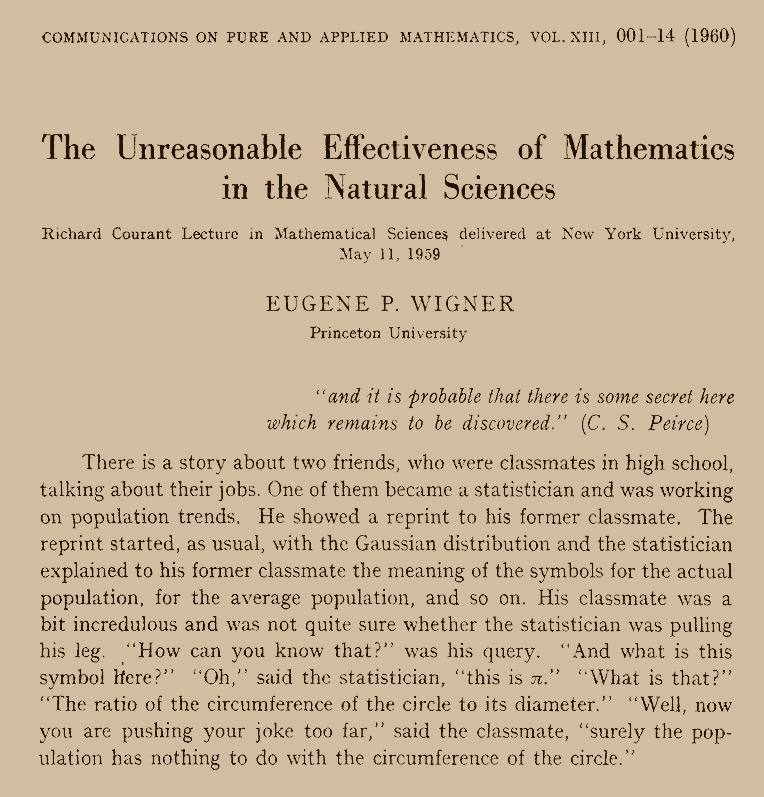

Sixty years ago, the physicist Eugene Wigner wrote an article with the title The Unreasonable Effectiveness of Mathematics in the Natural Sciences. Eugene Wigner, The Unreasonable Effectiveness of Mathematics in the Natural Sciences Communications on Pure and Applied Mathematics 1960, 13(1): 1-14. In the article, Wigner claimed that mathematics is extraordinarily successful as the basis of so many scientific theories, even claiming that its success is a “miracle”.

Since that time, Wigner’s ideas seem to have found a following among people who wish to see a deeper meaning in mathematics. They postulate that it seems utterly extraordinary, that if mathematics is simply a collection of humanly constructed theoretical concepts which do not refer to physical things, that it should be the underlying basis of nearly all scientific theories. And they assume from their inability to explain this mathematical basis of science, that there must surely be some mysterious non-physical connection between mathematics and the real physical world.

There is a striking analogy between that notion and a theist apologist’s assertion that the unexplainable can only be attributable to a deity - the “God of the gaps ” argument.

And to support their assertion, they will cite examples of where a mathematical idea had been invented many years before it was found to have a useful application in some real world scientific theory. They will point to those instances and say,

“Isn’t that amazing!”

Well, no, it isn’t. Objective analysis is required here, not a reliance on anecdotes. If you cherry-pick the mathematical concepts which are in fact used in science and technology, and ignore those mathematical concepts for which there has never been any useful application in science or technology, then your argument is suspect. In the same way, if you were to cherry-pick those instances where astrological predictions turn out to be correct, and ignore those instances where it has been incorrect, any claim that this might indicate that astrology is a scientific pursuit would quite rightly be rejected.

So, is the notion that mathematics is unreasonably effective in real world scientific theories just another instance of cherry-picking - seeing what you want to see – by attributing more importance to coincidences than is warranted – or is there something more to it?

Well, it doesn’t take long to discover that Wigner’s notion is irredeemably flawed – because it conveniently ignores a huge swathe of mathematical ideas that have never found any applicability in real world scientific theories.

One can easily observe that there is a very sizable chunk of modern mathematics for which there has never been any useful application in science or technology - or perhaps that chunk should be called, ‘notions that are called mathematical’. For example, in mainstream set theory,

The standard set theory used today is called Zermelo-Fraenkel set theory, after Ernst Zermelo and Abraham Fraenkel, who devised the theory in the early 20th century. It comes in several varieties, which you might find surprising when the proponents of set theory claim that set theory is the one true fundamental theory of mathematics. One variety includes what is called the Axiom of Choice, which essentially assumes that even if one cannot define a set whose elements are taken from infinitely many sets, don’t worry - there exists a metaphysical entity that will do it for you, and so, such a set “exists” (see also The Axiom of Choice). Another variety of set theory asserts that the Continuum Hypothesis is true. So you can have a set theory where the Axiom of Choice applies and where the Continuum Hypothesis is true, and a set theory where the Axiom of Choice does not apply and where the Continuum Hypothesis is true, and so on… . Also note that there are several other similar set theories have been proposed as being better than Zermelo-Fraenkel theory.

For more, see the pages that give an overview of set theory, starting at Overview of set theory: Part 1: Different types of set theories. there is a proof of a theorem called The Banach-Tarski theorem, and this theorem states that, given a sphere of a certain size, that single sphere is equivalent to two spheres of the same size as the original sphere.

The Banach-Tarski paradox is a theorem that states that, given a solid sphere, there exists a method in set theory that can take apart the sphere into a finite number of distinct pieces, which can be put back together in a different way to give two identical copies of the original sphere.

So, if we were to use that set theory without restriction, we would have a physical theory that asserts that a ball of a given size is equivalent to two balls of that same size. One wouldn’t call this theory a demonstration of the unreasonable effectiveness of mathematics in its applicability to science of the real world. Indeed we would remark on the converse, and point out how far the theory is removed from reality. And that is because such set theories have an irredeemable contradiction, see The Inherent Contradiction of Non-Natural Set Theory.

It has been claimed that if you restrict your working by some convoluted maneuvers so that you are not invoking a part of your set theory, the Banach-Tarski paradox can be side-stepped (Alex Simpson, PDF Measure, randomness and sublocales, Annals of Pure and Applied Logic 163.11, 2012: 1642-1659, also Leroy Olivier, PDF Theorie de la mesure dans les lieux reguliers ou les intersections cachees dans le paradoxe de Banach-Tarski, 1995). This makes rather questionable the claim that Zermelo-Fraenkel set theory (with the Axiom of Choice) is the one true correct foundational basis of mathematics when you have to deliberately avoid referring to some of its results when you are trying to apply it to a real world physical situation because otherwise you will end up with contradictions. It also throws cold water on the suggestion that set theory is unreasonably effective as a mathematical basis for science.

It is also worth noting that according to another mathematician of the same era, who was well acquainted with both Zermelo and Cantor, Zermelo was never fully satisfied with his version of set theory, writing:

Since Zermelo gave a proof of the well-ordering theorem, we have known that there are no other cardinal numbers than the Alephs. With this an undreamt-of deep insight into the essence of the infinite is gained, almost too deep for the human spirit. No wonder that this bold flow of thought leads to paradoxes. The question of which restrictions must be introduced in order to remove the paradoxes is difficult to resolve. Zermelo’s attempt in this direction remained flawed, as the great researcher himself admits.

From the autobiography of Gerhard Kowalewski (1876 - 1950), Bestand und Wandel, Oldenbourg Wissenschaftsverlag, Munich 1950, p. 250, my translation.

Looking at the matter dispassionately, it’s quite easy to see that Wigner was simply choosing those instances where mathematics is effective and ignoring the huge mass of what is called ‘mathematics’ that simply isn’t scientifically effective. And the real reason why we might observe that so much of mathematics forms the underlying basis of so many scientific theories is simply because the chunk of mathematics that has actually been used in real world applications is a mathematics that has grown from its origins in empirical observation of the real world. Natural numbers arose from observation of the real physical world, and from that base, the rational numbers followed, and then irrational numbers, and then complex numbers, each following in a logical progression as solutions to equations generated from the numbers previously defined - and all these numbers have useful real world applications - modern science and technology would be impossible without them.

About 150 years ago Georg Cantor invented his set theory and his transfinite numbers (see Cantor’s transfinite numbers), not as solutions to equations generated from the numbers that were previously defined, but as an invented concept which owed much to his religious beliefs (see Cantor’s religious beliefs) and which was inherently contradictory - a core concept is that a limitlessly large set can be smaller than another limitlessly large set (see One-to-one Correspondences and Properties, and also Proof of more Real numbers than Natural numbers? and Why do people believe weird things?). And despite no useful scientific or technological application having being found in the 150 years since Cantor came up with his invented numbers, the contradictory theory that invokes those transfinite numbers remains as the crumbling foundation stone of a large branch of modern mathematics. Despite its inherent contradictions, its proponents claim that it alone is the one true foundation of all mathematics.

So perhaps the way you might answer the question, “Is mathematics unreasonably effective in science?” depends on whether you think the contradictory theory of sets of transfinite numbers is actually mathematics.

If you think it is mathematics, then your answer will probably be no, it isn’t unreasonably effective in science, since there’s a huge chunk of it that has no applicability whatsoever to science.

On the other hand, if you think that this contradictory theory isn’t real mathematics, then your answer is also that mathematics is not unreasonably effective in science - yes, it is effective in science, but there’s nothing surprising or ‘unreasonable’ about that - it’s effective for a very simple reason - because it arose from empirical observation of the real world.

For another interesting but somewhat alternative approach see The Unreasonable Effectiveness of Metaphor by Julie Moronuki, although when she talks about basing the concept of sets on physical containers, she doesn’t remark on the fact that while one can have multiple empty containers inside one container, this is impossible in standard set theory - which may be something to do with why standard set theory is not amazingly effective in many real world situations.

Hamming’s “Unreasonable Effectiveness of Mathematics”

In view of the evidence that the human invention of numbers came directly from observation of the physical world, it is mind-boggling to see in an article by R W Hamming that follows in Wigner’s footsteps, a comment such as: R W Hamming, PDF The Unreasonable Effectiveness of Mathematics, The American Mathematical Monthly 87.2 (1980): 81-90.

“Is it not remarkable that 6 sheep plus 7 sheep make 13 sheep; that 6 stones plus 7 stones make 13 stones? Is it not a miracle that the universe is so constructed that such a simple abstraction as a number is possible? To me this is one of the strongest examples of the unreasonable effectiveness of mathematics. Indeed, I find it both strange and unexplainable.”

One is given to wonder if the author would think it less strange if 6 stones and 7 stones would make 9 stones? Or if on one occasion they would constitute 9 stones, and on another occasion 10 stones? To find it surprising that 6 stones plus 7 stones make 13 stones is to consider it surprising that the physical world is as it is, rather than it being a fantasy world where magic is commonplace.

Other Posts

Rationale: Every logical argument must be defined in some language, and every language has limitations. Attempting to construct a logical argument while ignoring how the limitations of language might affect that argument is a bizarre approach. The correct acknowledgment of the interactions of logic and language explains almost all of the paradoxes, and resolves almost all of the contradictions, conundrums, and contentious issues in modern philosophy and mathematics.

Site Mission

Please see the menu for numerous articles of interest. Please leave a comment or send an email if you are interested in the material on this site.

Interested in supporting this site?

You can help by sharing the site with others. You can also donate at where there are full details.

where there are full details.